Orchestra History

History

(1880s–1910s)

The Detroit Symphony Orchestra performed its first subscription concert on December 19, 1887 at the Detroit Opera House. Several conductors helmed the orchestra in its shaky early days. By 1900 Hugo Kalsow was appointed the music directorship, and he held the position until the orchestra ceased operations in 1910.

Three years later, a second try: ten Detroit society women each contributed $100 (approximately $2,500 today) and pledged to find 100 additional subscribers to donate $10 to fund a new iteration of the DSO. They organized quickly and successfully, and when the money was raised Weston Gales was appointed music director for a concert season beginning in February 1914.

Gales left the podium in 1917 and was succeeded by an acclaimed Russian pianist fresh off a stint with the Boston Symphony Orchestra: the tall, wild-haired Ossip Gabrilowitsch. A friend of Gustav Mahler and Sergei Rachmaninoff, and son-in-law of Mark Twain, Gabrilowitsch brought instant credibility to the DSO.

(1920s)

Gabrilowitsch also brought a demand: a new, suitable concert hall for the orchestra. Orchestra Hall, designed by renowned theater architect C. Howard Crane, was built in just four months and 23 days during the summer of 1919. “So much enthusiasm has been shown in the new auditorium…in keeping with the prominence to which the constructive work of Ossip Gabrilowitsch, the conductor, has brought the Detroit Symphony Orchestra,” wrote the Detroit Free Press.

The hall opened with a sold-out concert on October 23, 1919, and so began a decade of rapid growth and artistic achievement. Helmed by Gabrilowitsch, the DSO became one of the most prominent orchestras in the country. In 1922 it became the first orchestra to broadcast a concert on the radio. In 1928 it performed at Carnegie Hall and made its first recording.

(1930s–1940s)

The Great Depression emptied seats and created doubts about the future of the orchestra. Financial problems crept in and were exacerbated by Gabrilowitsch’s death in 1936; the DSO left Orchestra Hall in 1939. But the 1930s and early 40s also saw the DSO become the country’s first official radio broadcast orchestra (on the Ford Symphony Hour radio show, active from 1934–1942) and the release of several acclaimed recordings.

Further impacted by the United States’ entry into World War II, the DSO disbanded in 1942. Two years later, as the end of the war was nearing, wealthy patron Henry Reichhold resurrected the orchestra and installed Karl Krueger as music director. By this time the symphony no longer played at Orchestra Hall, which had become the Paradise Theatre; their home stage was at Music Hall on Madison Street.

After years of bickering with their colleagues, Reichhold and Kreuger resigned from the DSO in 1949 and the symphony disbanded again.

(1940s)

Orchestra Hall sat vacant from 1939 to 1941, but under the ownership of Ben and Lou Cohen it entered a new era under a new name: the Paradise Theatre. The revamped venue became one of Detroit’s premier stages for jazz, blues, and R&B performers throughout the 1940s.

The theater got its name from Paradise Valley, the area just across Woodward Avenue that was home to a large percentage of Detroit’s African American community and the city’s principal Black entertainment district. The Paradise was as important to Detroit as the Apollo Theater is to Harlem.

Opened with a concert by Louis Armstrong on December 26, 1941, the Paradise Theatre hosted superstars like Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, Ella Fitzgerald, Cab Calloway, Pearl Bailey, and many more. Its decade-long run ended in 1951, when it closed as the big band era waned.

(1950s – 1960s)

After two years of symphonic silence, John B. Ford recruited the Frenchman Paul Paray to lead a new, resurgent DSO. Paray was hugely popular and hugely successful as music director—he brought a French touch to his conducting style and ushered the DSO into a golden age of recording. Many of Paray’s 1950s and 60s albums with the DSO are considered some of classical music’s finest, and they attract dedicated fans decades later.

Paray conducted the orchestra mainly from the Masonic Temple (and sometimes from Orchestra Hall, where most recordings were made) until 1956, when the DSO moved to the riverfront Ford Auditorium.

(1970s–1980s)

Orchestra Hall changed ownership several times after the Paradise Theatre closed in 1951, and while it was somewhat regularly used it had fallen into serious disrepair by 1970. When word came that the once venerable hall would be demolished to make way for a department store, local citizens led by DSO bassoonist Paul Ganson rallied to save the building. Following a series of marches, several sidewalk performances, and tireless advocacy, the Save Orchestra Hall coalition of musicians, DSO fans, and concerned Detroiters successfully fended off the wrecking ball.

Meanwhile, at Ford Auditorium, the DSO was playing as well as ever. Sixten Ehrling conducted an incredible 722 concerts (the most of any DSO music director) between 1963 and 1973, leading the orchestra for 664 individual pieces of music. His successor, Aldo Ceccato, continued in the workhorse style. Antal Dorati and Günther Herbig succeeded Ceccato and re-introduced the DSO to the world through a second golden age of recordings and several international tours.

A restoration plan for Orchestra Hall was also underway. Basic upgrades like fixing the roof and replacing the carpet were made alongside painstaking repairs to intricate architectural details and decorative plasterwork. The process took nearly 20 years and cost more than $6 million, but it was worth it—and the DSO came home to Orchestra Hall in 1989.

(1990s–2000s)

In 1991, the DSO hired Neeme Järvi as music director and tasked him with leading the orchestra into an age of renewed vitality. He responded by doubling concert subscriptions, tripling broadcast syndication, and earning rave reviews for a new set of DSO recordings.

A bold vision for the DSO’s Midtown Detroit campus was also formed in the Järvi years. This vision was realized with the completion of the Max M. and Marjorie S. Fisher Music Center in 2003; The Max is a 130,000 square foot expansion of Orchestra Hall that includes new venues, atrium space, an education wing, administrative offices, and more. It still proudly serves as the home of the DSO and Orchestra Hall today.

(Present)

Leonard Slatkin was appointed music director in 2008 and helped envision new, groundbreaking ideas as the DSO emerged from a strike in 2011. The orchestra lowered ticket prices, embraced innovative programming, and placed accessibility at the core of its mission.

The Live from Orchestra Hall series, which offers free, live webcasts to fans worldwide, is the first (and only) initiative of its type among major orchestras and is now a point of inspiration for the future of arts accessibility. Programs like chamber recitals and the William Davidson Neighborhood Concert Series bring DSO musicians closer to audiences across Metro Detroit, while innovative performances in The Cube enrich Detroit’s musical landscape.

Now, as Detroit resurges and the world changes, the DSO enters a new era of possibility. Jader Bignamini was introduced as the 18th music director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra in January 2020. The DSO’s 2023–2024 season marks his third full year as DSO Music Director, and his infectious passion and artistic excellence have set the tone for the DSO on stage, establishing a close relationship with the orchestra and creating extraordinary music together.

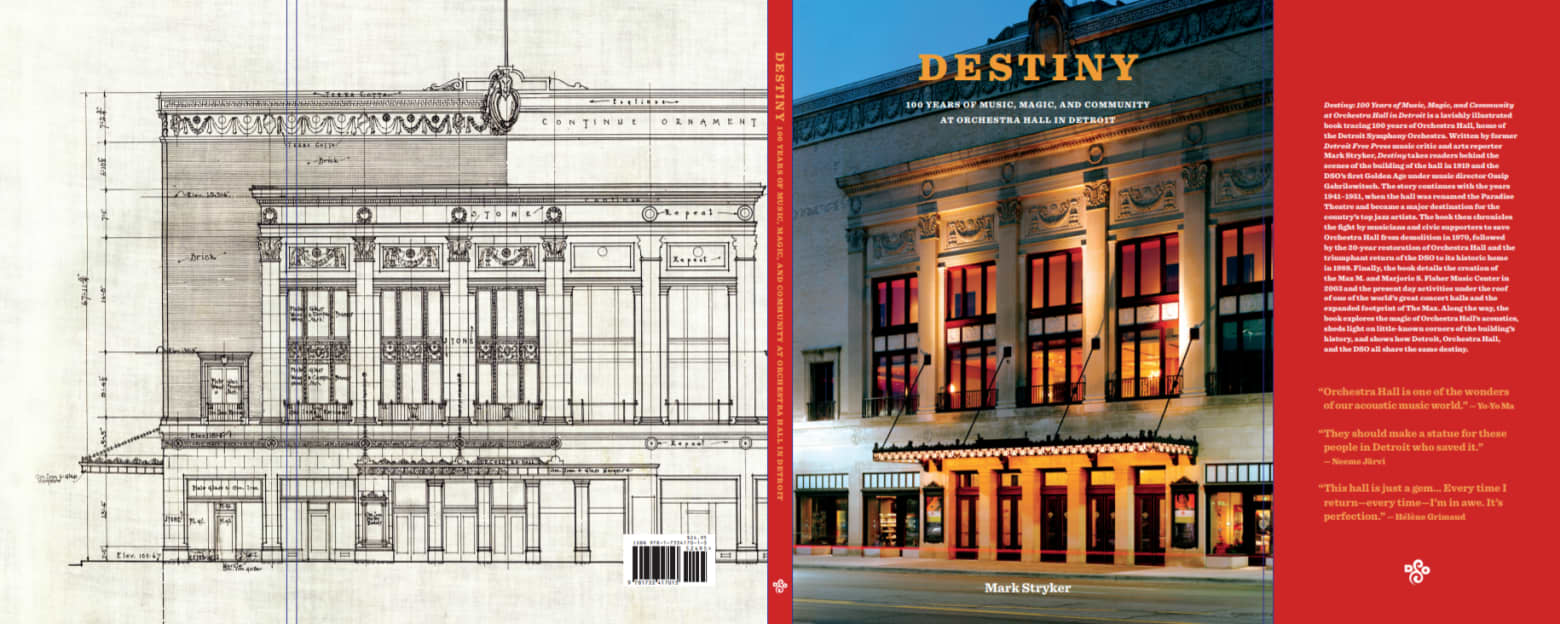

Destiny: 100 Years of Music, Magic, and Community at Orchestra Hall in Detroit

A 150-page, lavishly illustrated coffee table book written by former Detroit Free Press music critic and arts reporter Mark Stryker, Destiny traces 100 years of Orchestra Hall, home of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Stryker takes readers behind the scenes of the building of the hall and the DSO’s first Golden Age under music director Ossip Gabrilowitsch. The book then explores the Paradise Theatre years from 1941-51, the fight to save the hall from demolition by musicians and civic supporters, the restoration and return of the DSO to its historic home, the creation of the Max M. and Marjorie S. Fisher Music Center, and what may lie ahead for one of the world’s great concert halls. Along the way, the book explores the magic of Orchestra Hall's acoustics, sheds light on little-known corners of the building's history, and shows how Orchestra Hall, the DSO, and Detroit all share the same destiny.

Please check back for purchase information.

Mark Stryker’s engagement as author of Destiny: 100 Years of Music, Magic, and Community at Orchestra Hall in Detroit was generously underwritten by Ann and James B. Nicholson.

Additional support of this commemorative publication was underwritten by the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan and Ford Motor Company Fund.